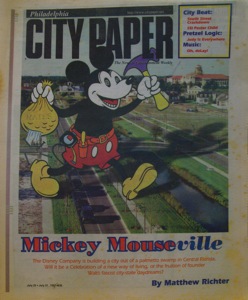

A review of Disney’s Celebration, Florida and the planned community movement

Originally published in The Stranger, seattle

Subsequently published in numerous regional weeklies and in “Introduction to Geography,” published by American Heritage

Place, Inc.

Reinventing the Company Town

Matthew Richter

Central Florida wasn’t ever a pretty place, not the way God made it, anyway. The flat hot monotonous stretches of sandy dry craggy underbrush and angular, bare pines are in start contrast to the beautiful nooks and crannies of the Gulf Coast, the glamour of Palm Beach, or the swampy lushness of the Everglades.

We’re on Highway 4, headed north through the heart of Central Florida toward the Walt Disney Company’s fully owned and operated private town, Celebration. We slow for what looks at a distance like road work on the median—there are three orange-vested guys dragging a dead eight- or ten-foot alligator onto the back of an Osceola County pickup truck. The gator, I can only guess, was living in the swampy drainage ditch between the north and south sections of the highway.

I grew up in Florida, and my family would drive within 5 or 10 miles of the future site of Celebration a couple of times a year on our way to and from my grandparents’ place on the other side of the state. The town of Kissimmee was the halfway point of the trip, and in the mid-‘70s consisted of little more than a rodeo ring, a flying school, a McDonalds, and two or three motels. It had a hick feeling to it, a reminder that most of Florida still wasn’t anywhere near an urban center. Today Kissimmee, two miles from downtown Celebration, has sprawled into a long, unbroken corridor of waterslides, motels, RV parks, 7-11’s, strip bars, and gas stations. It’s still a hick place—just bigger.

“Eisner said, ‘Well, you can build a town, but it has to be a special place,” says AnneMarie Matthews, publicist for the Celebration Company, and a Disney employee. “And that’s where our cornerstones came from.” We’re standing in the lobby of the preview center in Celebration, Florida: population 808, zip code 34747. “We’re founded on five cornerstones,” AnneMarie continues, “and they are Education, and you see that in the school and teaching academy; Technology which is the website and server; Place, which is the architecture; and Community, which kind of is that sense of… community. That’s kind o been lost for a while, but now we’re gravitating back toward that. Those are our five cornerstones.”

Now Education, Technology, Place, and Community only add up to four cornerstones (Health is the fifth, that’s the hospital). But the cornerstones represent a sort of mission statement, and they are all this population of 808 has to hold them together in the middle of the Florida wetlands. The full build-out for Celebration (8,000 homes, or 24,000 people) is planned for sometime 15 or 20 years down the line, taking this for-profit urban experiment will into the next century.

L.A. AUG. ‘65

The roots for Celebration’s master-plan can be traced back more than 30 years, to Los Angeles, California in the late summer of 1965. The Watts race riots are raging out of control. Before they’re over, 34 people will be dead, and the city will rack up more than $40 million in property damages. People think America is falling apart.

Holed up in a secret office in Burbank, just 20 minutes from the heart of the riots, CIA operative Walter Elias Disney—the abusive, racist, sexist, anti-Semitic alcoholic genius and family entertainment mogul—is starting to die from lung cancer. The walls of this secret windowless room are covered with drawings and maps. The desk is littered with lists of statistics on crime, health care, employment and municipal demographics. There are architects’ visions of Utopian communities and master-planned cities leaning on easels. There are photos of Washington, DC and Paris; there are models of monorails and domes cities full of looming skyscrapers. Disney is desperately trying to solve one last problem before he goes.

“Roosevelt called this the century of the common man,” Walt said, according to biographer Leonard Mosley. “Balls! It’s the century of the Communist cutthroat, the fag, and the whore.” The Communists, fags, and whores of the baby boom were taking over America’s urban cores while the monotonously prefabricated Levittowns, Broadacre Cities, and trailer parks of suburbia were taking over everything else. America was becoming an ugly and unfriendly place to live. In 1962 Disney decided to build himself an apartment above Main Street USA in Disneyland. In 1965 he developed and designed the Experimental Prototype Community of Tomorrow, a name that was eventually stenciled on the door of that secret Burbank office.

“EPCOT,” Walt said at the first press conference held to announce the plan, “will be a place unlike any other area in the world, where people actually lice a life they can’t find anywhere else. It will be a planned, controlled community, a showcase for America.”

He saw a future of gleaming skyscrapers and noiseless, non-polluting monorails. He saw a domes city where technology would set us free, and he saw a well-researched, well-conceived urban master-plan making people happy. “It just happens that I’m an inquisitive guy,” he told reporters, “and when I see things I don’t like, I start thinking, why do they have to be like this? How can I improve them? In EPCOT there will be no slum areas, because we won’t let them develop. There will be no landowners and therefore no voting control. There will be no retirees: everyone must be employed. One of the requirements is that the people who live in EPCOT keep it alive.”

Within a year of the press conference, Walt was either dead or cryogenically frozen, depending on who you talk to. Either way it doesn’t much matter, his brother and successor Roy Disney, who had often complained about the “goddamned madness that got into Walt when he decided to make a city out of this awful swamp,” immediately scrapped all plans for the urban experiment.

And so we jump ahead to April of 1992, to the Walt Disney Company’s international headquarters in Los Angeles, California. Outside, the Rodney King race riots rage out of control. Before they’re over 42 people will be dead, with over $1 billion in damages. Now people know America is falling apart. Inside, Michael Eisner, the 55-year-old, Semitic, Chairman and CEO of Walt Disney Company, is poring over plans to resuscitate Walt’s Utopian vision.

He is looking at plans to turn a 10,000 acre parcel of the 30,000-acre Disney holdings in central Florida into Celebration, the country’s largest master-planned community, at a reported cost of $2.5 billion.

PLACE, INCORPORATED

Celebration is part of the new wave in suburban development, a design philosophy in high vogue these days known as New Urbanism. Disney now owns their functioning New Urbanist town in central Florida, while here ins the Pacific Northwest, Port Blakey Communities, Inc. has just broken ground on their New Urbanist Community of Tomorrow, 25 minutes from Capitol Hill on the burgeoning Sammamish Plateau.

New Urbanist communities are prototypes for a new way of living, a cross between the eco-tech Biosphere bubble in the Arizona desert and the small-town domesticity of Bob Dole’s Russell, Kansas. Primarily developed and marketed by Miami architects Andres Duany and his wife Elizabeth Plater-Zyberk, this approach is supposed to be the alternative (solution?) to the crime and pollution of the city and the anonymous stupor of the suburbs. Duany himself has become something of a cult hero in urban planning circles, famous for L. Ron Hubbard-esque platitudes like, “Suburban codes attempt to impose order; neotraditional codes avoid disorder.”

New Urbanists are following an historic precedent laid down by previous generations of community planners and architects. Fifty years ago the architect Le Corbusier wanted to raze the entire Left Bank of Paris to build his revolutionary and Utopian Radiant City. In the ‘30s, Frank Lloyd Wright foresaw a glorious Broadacre City of highways, billboards, and strip malls covering the country from coast to coast in a uniform grid. In 1963, the Rouse Company in Maryland acquired about 15,000 acres of farmland to build Columbia, their masterplanned city of recreation, with 54 tennis courts, and 18-hole golf course, 25 swimming pools (four indoor), and equestrian center, 2,700 acres of parks, and 5,000 acres of green belt. Columbia still exists, with, at last count, 79,000 residents.

You can get on the Internet and find a whole subculture of Utopian Web sites. There’s the Oceana site, dedicated to establishing a new Utopian country—an aquapolis, a floating island of concrete and steel anchored somewhere in the Caribbean. Oceana passports are now available at the introductory price of $150.

Like their predecessors, Duany and his New Urbanist colleagues are constructing their cities from scratch in an attempt to rebuild community from the architecture up. They are building physical manifestations of the mythic Americana suggested by Norman Rockwell, Frank Capra, and Disneyland’s Main Street, USA.

They are also part of a movement that private business is making deep into the municipal realm across the country and across pop culture. Companies owning cities is a concept that has been explored in a ton of science fiction: there’s the evil company town Martian colony of Total Recall and a private foreclosure on Detroit in Robocop II (or was it III?). There are Coca-Cola’s off-world colonies in Blade Runner and the worldwide Company-State that emerges after Rollerball’s Corporate Wars.

In Seattle, private black-shirt security officers with no municipal accountability already patrol Pioneer Square and Belltown. Our news editor tells me my power bill will soon come to deregulated, privatized companies. Fire department aid cars have been replaced by private companies’ ambulances, and companies like K-III Communications’ Channel One are making bids to own and operate public schools.

In 1991, the federal government couldn’t afford to send the original copies of the Bill of Rights they had on tour for the for the document’s 200th birthday. They sent letters out to thousands of private companies and foundations asking if anyone was interested in sponsoring the tour. They got one response: The Phillip Morris Company. The tour was a success—the Bill of Rights trotted from city to city, hydraulically rising up in a Plexiglas bubble to inspirational music, night after night.

Phillip Morris also sent, to any Marlboro smoker who wanted one, a copy of the document, printed on parchment paper and suitable for framing, as part of their “Smoker’s Bill of Rights” campaign.

As the line blurs between the public and the private, the municipal and the corporate, Americans have an interesting choice to make. Often private companies are the only ones who can afford to do the things that governments used to pay for. Are we willing to cede municipal control to an un-elected for-profit entity just because they can get the job done?

TRADITION… TRADITION!

Faron Kelly is the Special Events Coordinator for Celebration, Florida, and as such is the company’s point person for Cornerstone #1: Community. “I’m a big piece of that,” he says. Faron is young, enthusiastic, and great-looking. He started in the entertainment division of the Disney theme parks, and transferred here when his manager also moved. “A lot of things that I’m doing, sure, they’re marketing events designed to draw traffic, but they’re traditions. I grew up in a small town in Iowa of about 900 people, and I draw from that background. I look at that, and it’s like, I’d life to bring that to Celebration. That’s the feeling that Celebration has fore me: it’s community, it’s tradition.”

The town celebrates its second annual Founders Day this November with a town photo on Market Street, a picnic near the gazebo in Founders Square, and a five-kilometer run through the city, from Savanna Square to Veranda Place and beyond. Founders Day commemorates the day in 1995 when a lottery was held to see who of the thousands who were interested would be chosen to move into the first 473 units in Phase One of the Celebration development. “In November ’95 we decided to have a drawing for Phase One,” says AnneMarie. “Instead of having a long line, we wanted the drawing to be a pleasant experience, versus, you know, a non-pleasant experience. So we had carnival games and balloon people, and just kind of made it a fun day, versus, you know, not pleasant.” AnneMarie also doubles as editor-in-chief for the Celebration Chronicle.

Faron and AnneMarie are charged with helping a group of people create a community, a group that has in common only that they all want to live in this kind of place. Faron and AnneMarie are helping to invent traditions on what five years ago was nothing but old pastures and wetlands. They are trying to create a sense of history without a past. Residents want to take pride in their community and their values… but first they have to invent them.

Almost everyone I spoke with used the word: “One of the things we love is the values that the city has. I feel safe here, I feel comfortable here,” or, “It’s a city that’s got values, and you just don’t see that nowadays.” “You hear people talking a lot about values here,” says another, “because people have values here.” But no one can explain what those “values” are.

At the EPCOT theme park, there’s a ride called Journey Into the Imagination. It doesn’t celebrate what you imagine—not pirates or ghosts or treehouses or princesses in their castles—it simply “celebrates the human imagination.” It made the chorus to the ride’s song easy enough to remember: “Imagination, imagination, imagination, imagination!”

Now, promoting “imagination” without evoking anything to imagine is fine, if a little wishy-washy. But unfortunately “values” is a loaded word today. You have to wither specifically articulate what values you’re talking about or assume that people will add the words “Republican family” to your values.

“It’s interesting,” says Brent Harrington, manager of Celebration’s Town Hall, “because you do hear people talking a lot about values, and I’ve yet to find anywhere where anyone has put down a list of our 10 values. I think what it’s more about is that Disney articulated a compelling vision. When you move into Celebration, so much is already in alignment with your neighbors. You knew very much about what you were getting into. You moved here because you knew what it was going to be like, and people who aren’t interested in that sort of thing are going to go elsewhere. It’s that sense of alignment that is most striking.”

“You have to have a real tolerance for ambiguity to live in Celebration right now,” says Jackson Mumey, a resident and member of the Celebration School Dream Team (Cornerstone #2: Education). Jackson and I met randomly downtown. He’s a self-described “old-school lefty” with two kids in the Celebration school and a house being built—“My countertops didn’t arrive again today”—just a few blocks from the park where we sat down to talk. “We’re really in an ambiguous startup mode. It’s all new to everybody. Some people have come and been really frustrated with that ambiguity.”

There are other confusing ambiguities in Celebration, and a few seeming contradictions. The hospital can’t really be called a hospital, because it has no beds. It’s more properly referred to as a Wellness Center, with one doctor (Dr. Stone) and a fitness club (Cornerstone #3: Health). The school (to which Disney has promised $5 million a year) is controlled by Osceola County, but the privately operated Teacher’s College right next door is set up to feed Disney-trained teachers into the system. And in perfect Disney style, the antique-looking watertower at the entrance to town isn’t a water tower at all. “I’m not sure what’s in there,” says AnneMarie, “but it’s not water.”

My favorite contradictions and ambiguities in Celebration have to do with the Town Hall, designed by architect Phillip Johnson. The outside looks like a circa 1973 office building, with a forest of square metal columns holding up an enormous 20-foot eaves around a solid and bland brick box. But the inside evokes a totally different era. There’s heavy, dark wood furniture of walnut and darkened oak. There are props placed on the furniture, like the 1930’s-looking desk fan sitting on top of the bookcase. The office doors are all dark wood with clouded glass panels and names stenciled onto the glass. From the outside the building looks like a ‘70s bank; from the inside it looks like the office of the Bailey Building and Loan from It’s a Wonderful Life.

“We’re creating community through space and through the relationships of buildings, says Joe Barnes, the architect who oversaw the creation of the Pattern Book from which all of Celebration’s residential buildings are designed (Cornerstone #4: Place). “This is a place you can develop an emotional equity with.”

Even the home names invite you to create Barnes’ “emotional equity.” There’s the Sturbridge Classical, the Colonial Revival Cottage, the Victorian Charleston Siderow… When you buy in Celebration you pick from six basic house designs, with a myriad of detail options. The Pattern Book is a gorgeous document—enormous full-color pages bound in clothand covering the most minute details, from the size and position of finials to the different options for dressing up your front steps. Take a Classical Charleston, change the shutters and the size of the front door, and voila! You’ve just designed a Coastal Charleston.

Inside, of course, the houses look like almost any other prefab development interior. The facades are quaint and Victorian, painted in pastel colors that glow magically in the Florida sunset. Inside, they’re laid out to facilitate watching TV and sleeping.

Johnson’s Town Hall is also the seat of the town’s particular brand of democracy. Brent Harrington, as manager of Town Hall, oversees all governmental operations in Celebration. There are three governing bodies: two Community Development Districts and a Community Association. They are, in Harrington’s words, “true political subdivisions, a mini-government with all the normal rules of public elections, and the ability to levy taxes and control and maintain the infrastructure of the town.” Celebration’s rules and laws (along with the laws of the county and the state) are enforced by sheriff's deputies patrolling the roads, and augmented by private security hired by the Celebration Company. All three political bodies are elected by the town’s residents—or, more specifically, by the town’s property owners. Now, Jim Crow references aside, the vote-by-property-ownership arrangement has one catch:

“At this point I don’t know the exact number, but the Celebration Company still owns about 90 percent of the property,” Herrington says. “So obviously the developer can put in the people they want to have in there [in the government]. As time goes on and we grow, the balance shifts, and those folks [in the government] will be more representative of the residents and the business interests here. But it will be a good long time yet before the majority shifts to an outside party… So what the Celebration Company did was say, let’s not fool ourselves. Let’s hace meetings and talk about the issues, but let’s avoid the fiction of having to go through elections. We’ll just give ourselves the power as developers to appoint people, until there’s a certain percentage of lots sold, and then we’ll have elections. It’s a lot better way to do it. And it puts the accountability squarely where it belongs.”

But what Brent fails to mention is that control over the government will never shift away from the company, even after they start holding elections. According to Joe Barnes, “the company will retain the majority of the land, a little over half.” Between the greenbelt what surrounds the development, the retail and commercial cores, and other company-owned parks and buildings, Disney will always own more than half of the town. If voting is tied to the amount of property you own, Disney will always control at least 51 percent of the vote.

Celebration is following through on Walt’s promise of “no voting control,” except that people will vote.

“CELEBRATION” IS A NOUN

As Celebration builds itself up out of a palmetto swamp, it’s trying desperately to not look like it’s popping up our of nothingness. The company had the planet’s largest tree spade custom-built for the project, a monster of a machine that can pick up and plant a fully mature tree anywhere you need one. It’s a trick that works: the grownup trees lend an air of respectability to the otherwise obviously brand-new city.

“Disney set the stage for us,” says Herrington, “but we have to live in it. We have to make it work. Nobody here has any interest in living in a Stepford community. It’s really up to us to make it a cool town.”

The Stepford reference is one that lots of people in Celebration make defensively. It’s an interesting one—in Ira Levin’s 1972 novel The Stepford Wives, suburbia is a sterile, predatory place where one housewife believes that the Stepford husbands are covertly replacing real woman with big-busted, suppliant, housework-obsessed robots:

“Towns develop their character gradually,” Dr Fancher said, “as people pick and choose among them… I’m sure Stepford developed its character in the same way.”

Joanna, shaking her head, said, “If you only could see what Stepford women are like. They’re like actresses in TV commercials, all of them. They’re—they’re like—“ She sat forward. “There was this program four or five weeks ago,” she said, “My children were watching it. There were figures of all the presidents, moving around, making different facial expressions. Abraham Lincoln stood up and delivered the Gettysburg Address; he was so lifelike you’d have—“ Joanna sat still.

“Disneyland,” she said. “The program was from Disneyland.”

Dr. Fancher smiled. “I know, my grandchildren were there last summer. They told me they ‘met’ Lincoln.”

Joanna turned from his staring.

“I think you should consider trying therapy,” Dr. Fancher said.

“There are no wires in my back,” promises Mumey. “I promise I’m not animatronic. This isn’t Stepford. This is real.”

Community-builder Faron Kelley and I are finishing lunch at the golf club restaurant. Our waitress, Mary, wears a cast-member name tag (all non-executive Disney employees are called “cast members”). Faron, AnneMarie, Brent, and Joe are cast members. Dr. Stone is a cast member. The real estate agents are cast members. Mary disappears behind the Cast Members Only door to the kitchen as Faron and I finish our iced teas. Outside the windows, Black and Latino men in white shorts and pith helmets silently and artfully tend the perfectly manicured gardens surrounding the clubhouse. They’re cast members too.

“Celebration is an attempt to get back to simpler times,” Faron says, “times when people didn’t worry about things. They didn’t just go into their houses lock their doors and never meet their neighbors. People really want to be involved here, they’re all over this stuff. If I say we’re going to do a town-wide picnic, everybody shows up. People have a real passion for what’s going on. Everybody is just so excited for everything. They just eat it up. Give me more, give me more! It’s just great.”

Faron is also a founding resident of Celebration—a Celebration, a Celeb, a Celibate. No one has figured out what to call someone from Celebration yet. “It’s a challenging name from a marketing standpoint,” says Faron. “You say, ‘come to downtown Celebration’ and people think there’s an event, a celebration, going on downtown. I mean, why did we name the town a verb?”

25 PERCENT QUIRK

Disney, as I mentioned before, isn’t the only company that can play the community-building game, nor are they the only ones playing the game by New Urbanist rules. We now leave the sun-drenched man-made lakes of central Florida for the soggy man-made runoff ponds of the great Pacific Northwest. In the hills overlooking Issaquah and I-90, on a 2,200 acre plot of second-growth timberland purchased from Burlington Northern, backhoes, tractors, and dump trucks are busy reforming an overgrown wilderness into newurbia. Peter Strelinger from Port Blakey, Inc. and I are on our way up a construction access road to Grand Ridge, the company’s new New Urbanist development.

The access road takes us through what one friend calls “The Vastness,” the enormous, gray, disappearing hillside that is the Lakeside Industries Quarry. Just above The Vastness, Lakeside Industries is also quarrying gravel from the future site of Grand Ridge, carting it down the hill on loud, rambling conveyor belts that snake their way over the ridge to the pit. Stopping on what will soon be a road, we get out fo the truck for a stunning overview of Phase One, a 700-unit “pedestrian-oriented neighborhood village.”

Phase One is, right now, nothing but stakes stuck in the dirt to outline where roads and lots will be and black plastic hurricane fencing outlining future water reservoirs and runoff ponds. Those trees off to the right will be a park; retail is off to the left, the school is right behind us. The Space Needle is visible just past the next ridge, and Jay Buhner and Junior’s houses are down to the right, just outside the development.

When all is said and done, the 2,200 acre development will have developed only 550 acres of its land, preserving the rest as a greenbelt. There will be 3,250 housing units, 2.95 million square feet of commercial space in an office park, and 450,000 square feet of retail shops.

The Grand Ridge template is a 64-page spiral-bound book called the Grand Ridge Urban Design Guidelines, much like Celebration’s Pattern Book. In it are many of the same ideas: Garages to the rear of the lots, accessed through alleys (to get the garage door out of the front façade), are encouraged. Cul-de-sacs that end in a cluster of almost identical houses are discouraged. Small nooks of public space, with soft plantings and viewpoints, are encouraged. Deciduous shrubs directly adjacent to retail buildings are discouraged.

“The guidelines would prohibit a 7-11 from day one,” says Strelinger. “But it wouldn’t prohibit that kind of use, a close-to-the-neighborhood, walk-to-it convenience store.”

But how exactly would you keep the 7-11 out, without specifically naming them? The Evanston, Illinois, City Council decided in 1984 to outlaw the bagging of food in an attempt to keep fast food restaurants out of town. In 1986 the Burger King at Orrington and Church handed you a folded bag and a burger, and you bagged it yourself.

“There are a couple of mechanisms that do that [keep 7-11 and Burger King out]. Anyone who might propose a use like that, we’d have the tools to say, ‘No, that’s not appropriate. This is how it has to fit into Grand Ridge.’ But ultimately, all the site plans, all the uses, all the architectural plans go through us anyway. We have the last say on it.” He who has the land makes the rules.

There are design guidelines for different residential neighborhoods: the Hillside District, the Cottage Lane Neighborhood, the Traditional Townscape Neighborhood, and so on. There are photos of homes and parks that look like Fremont, Magnolia, and Madison Park in the “Encouraged” column, and photos of what could be my neighborhood “Murder Mart” convenience store, or the sprawl of North Aurora Avenue, in the “discouraged” column. Front porches, courtyards, and balconies are discussed; the height of fences and how to plant around them is laid out. Chapter Three explains that “approximately 75 percent of the lineal footage of one block front or street or alley” has to comply with the guidelines for a given type of neighborhood. “The remaining 25 percent may provide the ‘quirks’ that punctuate the pattern and soften the planned consistency.”

From the conceptual drawings, the town looks idyllic; shoppers stroll around open plazas with fountains while children frolic in the numerous parks and fields. KIRO Channel 7 rates Grand Ridge as one of the Hot Properties of 1997, and their “home expert” Tom Kelly predicts: “I have no doubt that people are going to snatch up those homes the instant they come on the market.”

WE VOTE WITH OUR FEET

“The biggest thing that has people leaving the cities and older suburbs,” says Peter Strelinger, “is a lack of a sense of community. You see a decline in the schools, an increase in crime, property values falling… In the older suburbs you see no integration of the neighborhoods, no mixing of uses. It’s like, you’ve got 150 houses by one builder, and they all look the exact same. Here, we’re creating a solid sense of community, a sustainable community that people can feel good about.”

Issaquah is already an odd mix of the remnants of different eras’ spastic fits of suburban sprawl. There are endless rows of cookie-cutter boxes in Klahani, an infamous development just outside Grand Ridge’s greenbelt. Gas stations, fast-food chains, low glass boxes of office buildings, and an Eagle Hardware megastore have clustered around the interstate exit like leeches drawn to an open wound. And then there’s The Vastness.

“Living near The Pit isn’t pleasant at all,” says one woman working near the plateau. “Issaquah was a gorgeous place before it was developed. It’s lost a lot of that beauty. And all of this has happened in just the last three years. It’s been almost instantaneous—there’s nothing ‘organic’ about this growth at all. Ands traffic, as you know,. Is a total mess.

“It can take you 30 minutes just to get from one end of town to the other,” says Strelinger. Traffic is a primary growth concern throughout most of King County, and Issaquah has plans for almost $80 million in new road work to begin this year, including one I-90 exit set for a $61 million expansion specifically to service Grand Ridge and the rest of the bursting-at-the-seams plateau.

There are strip malls, office campuses, 24-hour gas stations, and convenience stores permitted for construction in Issaquah this year. There are also townhomes, senior centers, a new city hall, and a new library in the works. This is the organic growth process of a city, finding its feet and its character and bending with prevailing development standards and philosophies. A city’s development over time leaves an urban fingerprint, sometimes chaotic and sometimes downright ugly. But you can look at this architectural fingerprint like the growth rings of a tree, picking out which were the good seasons and which were the bad.

There are two other New Urbanist developments in the works for Issaquah: the East Village and Parkpointe. Neither comes anywhere near the scale of Grand Ridge, but together the three developments represent almost three quarters of the city’s expected growth over the next 20 years—and Issaquah is growing faster than any other city in King County.

This all means one thing: If Ronald Reagan was right and Americans vote with their feet, then the people have spoken, and New Urbanist communities are where people want to live.

YOU NEVER HAVE TO LEAVE

“My car battery died,” laughs Faron Kelley in the golf club restaurant. I like quoting Faron. As director of Celebration’s celebrations, his pep is contagious. He lives in a charming house with his lovely wife and in the morning walks a mile in the sunshine to a job he adores. The bastard. “The car had just been sitting there for two weeks. I didn’t have to drive anywhere. It was great.”

One of the selling points of both Celebration and Grand Ridge is the idea that you never have to leave. “You could do everything here,” says Peter Strelinger. “We could be entirely self-contained; you’d never have to leave.” But this is a fiction; there are basic amenities that, at least in Celebration’s case, simply don’t exist in town. One of the reasons Faron might not ever get his car running is the fact that there aren’t any gas stations in Celebration, and there aren’t any plans for one. The supermarket has plastic red bell peppers in the display window, but inside the sparsely stocked store you won’t find any real ones. No one besides the cast members actually lives and works in Celebration yet (residents commute as far as Tampa, 80 miles away), and it’s a good bet that most of Grand Ridge’s population will be commuting either to Seattle or to the Microsoft campus.

You can’t even die in Celebration,” says one resident, in reference to the lack of inpatient beds at the Wellness Center.

To pretend that there’s anything urban about these developments is a joke. What these planners and developers have created is more appropriately New Suburbanism, just a different way of selling land within commuting distance of a major city. They are selling pre-packaged suburbia in proto-urban clothing, and as such the challenge here is the same challenge faced all across suburbia: creating something out of nothing and getting it to feel real.

The first American suburbs, close by and sometimes part of the cities they served, attempted to create a pastoral, rural feel; uninterrupted lawns side-by-side were meant to evoke the rolling hills and meadows of the countryside. Now we are pushing further out into real rural lands to create the look and feel of the proto-city.

I asked Jackson Mumey if the Celebration school’s curriculum had been adapted to incorporate some sort of orientation to what it’s like to live in Celebration—your average Social Studies class is going to confuse anyone old enough to know the difference between George Washington and Michael Eisner, and Celebration’s “executive branch” is perhaps not the kind of executive branch they’re talking about in Intro to Government.

“That’s a good idea,” says Mumey, “and I don’t know that anyone’s thought about teaching the kids that. I’m not sure that we even understand it.” You would think the citizens of Celebration would be excited to teach their kids about the great social experiment they are taking part in, about the historical context it fits into and the unique opportunities it presents. But these people are trying to convince themselves there’s nothing at all odd about how they’re living.

REPEATABILITY

“Everything we’re doing here is very repeatable,” says Celebration’s Joe Barnes. We’ve finished our architectural tour and now we’re sitting under a large oak at an outdoor café, drinking iced vanilla lattes, and I start to wonder who’s repeating whom. “You can repeat what we’ve done and use it to add to towns, to infill towns where you have a fabric you can wave into.”

And the ideas are spreading, not just to new developments. “The mayor of Milwaukee called and wanted to look at our design. A woman from the city of Schaumberg called and wanted to do the same thing,” says AnneMarie (who’s trying her first iced vanilla latte ever, and loving it). When cities start modeling themselves on models of cities, you know the word postmodern is going to be thrown around, and perhaps that’s what these developments are: perfectly self-reflexive communities, copied form a copy of an original that’s been all but forgotten.

“I think that much of what Celebration has done will be replicated in other places,” says Town Hall’s Herrington. “Scottsdale, Arizona has a development called DC Ranch that’s copying Celebration.” Grand Ridge is another good example—it wasn’t until I told Peter Strelinger that I’d been to Celebration that I think he really took me seriously.

“One of the things we’re trying to do here,” says Jackson Mumey, “is to have an impact beyond just this 5,000 acres. It needs to spread out, you know, you need to take the word to Washington, California, New York.” We’re sitting in Market Square, on a park bench across from a bubbling fountain. He’s shouting over the string of cement trucks and earth-movers passing behind us. A helicopter flies overhead showing the town to tourists, or prospective buyers, or a news crew. Apparently as many as four or five choppers fly over each day. Jackson gives up on shouting for a minute and we stare into the water. Then, in what is a rare moment of silence in Celebration, he says, “You don’t get a lot of chances to impact the world. We do this right, and it will have an affect all over the world. What better legacy could you have?”